Cassandra Tkachuk, PAg, CCA, MSc, Production Specialist – East, MPSG – Spring 2021 Pulse Beat

Keeping track of pests in pulse and soybean crops is something we prioritize at MPSG. We collect information through annual disease surveys, targeted insect monitoring, cyclical weed surveys, field scouting and by talking to our fellow experts in the field. Gathering up the facts, here’s what we would like you to know heading into the 2021 growing season.

Diseases

Root Rots

Root rots remain a top concern for soybeans, peas and dry beans for 2021. This includes Fusarium, Rhizoctonia and Pythium root rot for all of these crops, Aphanomyces root rot in peas and lentils, and Phytophthora root rot in soybeans. Based on provincial surveys over the past few years, root rot was found in virtually all fields, but not necessarily at high levels, according to our observations. This is a good thing, and our goal is to keep root rot levels low to minimize the impact on yield. Find detailed root rot survey results here.

The main defence against root rots is a diverse crop rotation, including at least four different crop types in sequence. Fungicide seed treatment is another defence if your field has a history of heavy root rot pressure, soil is saturated in spring and/or the rotation has been tight. MPSG’s On-Farm Network (OFN) has been comparing treated vs. untreated soybeans since 2015 on multiple farms and has found that yield responded positively to seed treatment 20% of the time (8/41 site-years). Note that trials were a culmination of fungicide-only or fungicide plus insecticide treatment vs. untreated.

With the rise and growing interest in pea production in Manitoba, Aphanomyces — named the most destructive pathogen of peas — is one to keep a keen eye on. Like other root rots, it prefers wet soil and can really take off if peas are grown too often in rotation. Current recommendations are to grow peas once every four years as a baseline practice and only once every six to eight years or longer if your field has tested positive for Aphanomyces. We recommend submitting plants for lab-testing if you suspect this disease.

SCN and SDS

The up-and-comer, soybean cyst nematode (SCN), ranks high on the priority list because of its positive identification in four Manitoba municipalities in 2019 and potential impact on yield. At this time, levels of detected SCN (found through the survey led by Dr. Mario Tenuta) are thankfully low. This means we can prevent it from becoming the problem it is in other soybean growing regions. Focus your scouting efforts in the low-yielding areas of the field. Random root investigation for cysts is also a good idea, as SCN can be lurking with no above-ground symptoms.

Starving SCN of its host crops (soybeans, dry beans, field peas and some forages) through rotation is the best way to keep the population low. Varietal resistance is another line of defence. But note that as this pest has moved in from other regions, we may also be inheriting its evolved ability to overcome the main source of genetic resistance (PI 88788) used for more than 20 years in the U.S. Rotating sources of resistance (e.g., with Peking) is highly recommended by our southern counterparts.

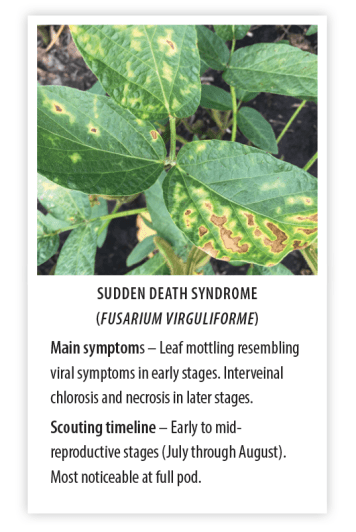

Sudden death syndrome (SDS), considered a stem and root disease, now makes the priority list of soybean diseases. Though its presence has not yet been confirmed in Manitoba, we are certain we’ve seen it on rare occasions. This pest seems to use the buddy system and has been reported in regions around the same time as SCN. It also closely resembles brown stem rot (BSR) — another disease not yet identified in Manitoba. So, we recommend vigilance and lab-testing of any suspected cases in 2021. We would love to hear from you if you think you’ve found SDS or BSR.

White Mould

White mould (Sclerotinia) remains a disease priority for dry beans in 2021. Your main defences against this one are rotation with non-host crops (e.g., cereals) and foliar fungicide if disease pressure is anticipated. Rainfall leading up to flowering is often the greatest influencer over development of the disease. This means there may not be a need for fungicide every year. Start looking for apothecia on the soil surface in late June/early July and follow our fungicide decision worksheet to determine if white mould will develop. Also, consider using a petal test at early flower to see if Sclerotinia DNA is present. These tests are offered by different companies for a cost but could end up saving you a lot of money.

OFN trials conducted from 2016 to 2020 (16 site-years in total) testing dry beans with and without foliar fungicide have revealed no yield differences to date. In most cases, the lack of response to foliar fungicide can be attributed to low white mould pressure. The OFN is set to continue testing fungicide in dry beans with a focus on economics.

Ascochyta/Mycosphaerella Blight

The Ascochyta/Mycosphaerella blight complex is high on the list of pea disease priorities. According to pea surveys, it is the most prevalent foliar disease in Manitoba and can have a significant impact on yield, making it the main target of foliar fungicide. Other lines of defence are crop rotation, varietal resistance and sourcing disease-free seed. Scout for purplish-brown flecks on leaves and pods and purplish-brown or black lesions on stems during the late vegetative stages through flowering (mid-June to late July). It will progress upward from the base of the canopy.

Pea yield response varies among farms when it comes to fungicide. OFN trial results from 2017 to 2020 have shown that single fungicide applications (vs. none) increased yield at 4/16 site-years and double applications (vs. single) increased yield at 3/7 site-years. When looking at economics, sometimes a double application pays, sometimes it does not. Our best recommendation right now is to follow the fungicide decision checklist for this disease, which accounts for symptoms and environmental conditions. And continue to monitor disease pressure to see if a second application is necessary 10–14 days later.

Insects

Soybean aphids make the insect priority list each year for soybean crops, whether or not they were a major pest the previous year. They move in from the south, making it difficult to gauge if they will be a concern for us in the coming year. If populations flare-up in 2021, read over our Soybean Aphids: Identification, Scouting and Management fact sheet to refresh your memory. This resource has been waiting in the wings since the last major flare-up in 2017, with information that is still up to date.

A very different type of aphid — the pea aphid — is a high priority for pea crops. Unlike soybean aphids, it doesn’t take very many pea aphids to do significant damage because of where they feed on the plant — the uppermost, yield-producing parts. Start looking for pea aphids at early flower and continue to monitor through pod formation and elongation. If the threshold is reached (two to three aphids per plant tip or 90–120 per 10 sweeps), insecticide options are available and ideally applied at the early pod stage.

Other insect priorities heading into 2021 are cutworms and grasshoppers in all pulses and soybeans, pea leaf weevil in field peas and potato leafhopper in dry beans. For a full insect outlook and details on these, refer to John Gavloski’s article.

Weeds

A couple of our top weed concerns for pulse and soybean crops heading into 2021 are tall waterhemp and kochia. According to the Noxious Weeds Act, tall waterhemp is a tier 1 noxious weed, meaning all plants must be destroyed if found. It was first identified in 2019 in four different municipalities in Manitoba. This weed is number one on our list because of its resistance to at least seven different herbicide groups in the U.S. and the fact that it is such a prolific seed-producer (average of 250,000 seeds/plant). The PSI lab now has a DNA test for identifying tall waterhemp in 2021.

Kochia also ranks high on our priority list because of its resistance to group 2, 4 and 9 (glyphosate) herbicides and its prolific seed-producing ability (14,000–30,000 seeds/plant). Plus, it’s a downright survivor — also known as tumbleweed, kochia was one of the only plants available for livestock to eat in the ’30s. This weed can thrive in saline patches in which pulses and soybeans cannot. It is also an early germinator, meaning plants are larger and tougher to kill at spray timing. Check out Laura’s article for tips on how to control it.

To guide you through, we have insect and disease scouting calendars for soybeans, dry beans, field peas and faba beans (brand new resource). These calendars give you a timeline of when to scout for each pest, the crop development stages it corresponds with and what its impact could be on production and quality. Find these and other resources mentioned at manitobapulse.ca/production.

Happy scouting!

You must be logged in to post a comment.